I don’t remember when I started reading books; I do remember they were often about animals, and they included poetry, pictures, artists, nature, and clothes. Not one of them missed a cat—and, of course, my favorite was called Slipper Keeper Kitty.

A legendary Slovenian picture book about a cat that takes children’s slippers when they don’t put them away after themselves. She sews them up and mends them, then returns them back later.

My mom has kept many of those books and the moment my nephew showed interest in stories, she brought them out of the basement. It was a beautiful journey back to childhood. There is a huge difference in how you look at your first book when you are a child—it awakens your curiosity, your fantasy and imagination, your creativity and most of all—your freedom. When you go back to the same illustrations and stories as an adult, the first thing you feel is nostalgia; oh to be a child one more time, to wake up at 11 am worry-free and with your favorite breakfast and storybook waiting for you.

But it’s not just nostalgia. You realize how much they have affected you and your character traits, your creativity, and even your style of writing or the art that you’re practicing as an adult.

As a toddler and kindergartener, I enjoyed spending time drawing and going through my picture books—and some of them—as much as my parents taught me to express my ideas in my sketchbook—are unfortunately marked forever with my abstract drawings.

I’m more than convinced these books and images helped me develop an affection towards visual art. As I grew, my mom continued to invest in drawing and painting books and encyclopedias, which, funny enough, served me more in the latter years rather than when she bought them, as I was then becoming more and more intrigued by the art of the written word and book covers.

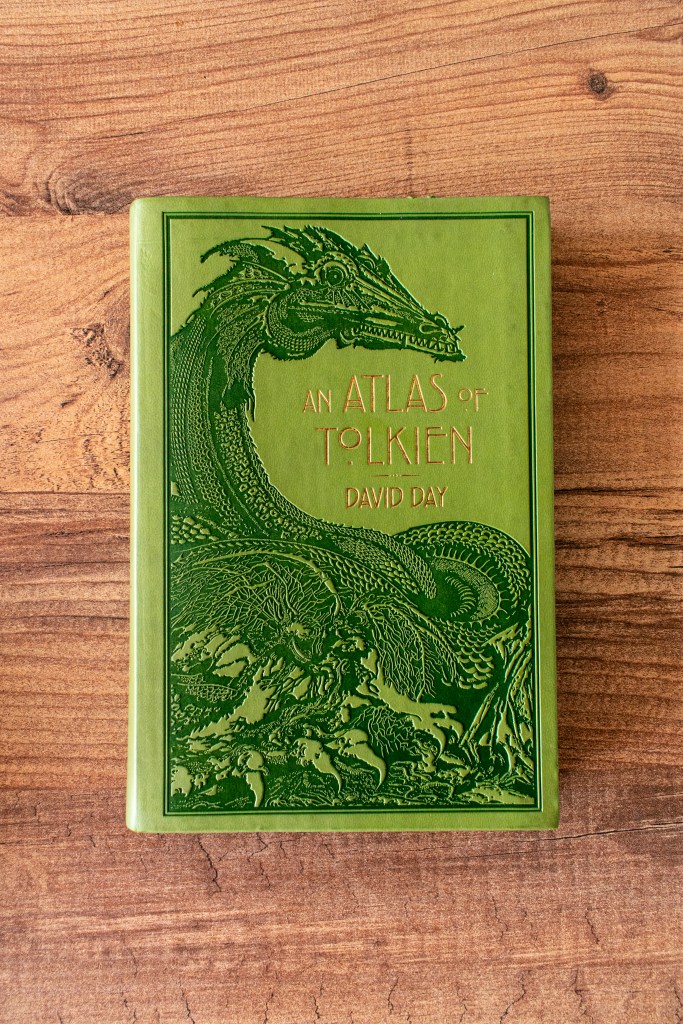

Somewhere around the age of twelve, I started paying more attention to our home library. My dad’s favorite encyclopedia, The Grand Larousse, was more often on the coffee table or in the dining room, rather than on the bookshelves—it was his dearest companion. I remember some of his other titles (out)standing with their French dignity among a mix of book genres. He mostly read non-fiction. As I write this, I realize how similar we are. I never avoided reading fiction, on the contrary—I have spent years digging deep through imaginary worlds, characters and situations, very much aware that many of them have existed somewhere and at some time.

However, the love of reality, knowledge, facts and being present in the now won. Like my father, I ended up filling my bookshelves with non-fiction; encyclopedias, social science and political books, research papers, world cinema, autobiographies, business and psychology, sport, and languages.

In contrast to my dad, my mom, a highly creative primary school teacher, in the need to take a break from academic papers, exams and science, would fill the bookshelves with thriller, romance, crime and psychology fiction.

I don’t remember a lot of details from those books as I would remember actual political or social situations, but there are books whose essence and weight I’ve carried with me throughout all these years. I rarely remember character names—I remember the emotions and thought patterns a book has awakened in me. I can easily recall the tension, curiosity and dread I felt while reading The Last Kashmiri Rose, or the fear, sadness, and strong presence of uneasiness while browsing through the pages of Doris Lessing’s The Fifth Child.

One of the books that I remember very vividly is Paulo Coelho’s Eleven Minutes. The miserable life of Maria (I had to Google the name) and the experiences she had after she entered the world of prostitution— I could empathize with her because I knew this isn’t just fiction.

A few years later, I walked the streets of Geneva and found myself on Rue de Berne—just as it had been described in the book. But seeing it in person felt heavier. The atmosphere was rough, the sadness more tangible. Behind glass windows stood women, motionless and deep in thought, waiting. They looked worn out, not just by the night, but perhaps by a lifetime of transactions that seemed to ask for what no one had a right over—the surrender of something deeply personal. I did not perceive Rue de Berne as a place to judge, but as a place of quiet exhaustion in need of love and understanding. A scene that, no matter how many times I read the romantic parts of Eleven Minutes, won’t disappear from my memory. And maybe for someone it’s easier to hide behind fiction and create their own world, where one’s suffering is presented as an opportunity and daydreaming.

I, however, chose to read and learn from reality.

I am forever grateful for these books that prepared me for what reality was to serve me—a world in need of books, authors, and realists just as much as it is in need of readers, fantasy and daydreamers.

Just a few days ago, I met with a compelling, down-to-earth person who was a refreshment in the sea of money-chasing, robotic individuals. Besides discussing professional matters, we delved into the current political and social affairs, the younger generations, ways of doing business, corruption, and the state of the written word.

“I gave up on this”, he said, alluding to local newspapers and digital magazines. “Whenever I open anything, it’s like they’re trying to bring you darkness. So I switched to laughing, you know,” he said, smiling with an almost disappointed look in his eyes.

“When I opened your text, the things you’re writing, I thought ‘Oh, thank God, there is someone who actually wants to say something.’ When I look at it, what you’re doing, what you’re writing about, one can notice that there is someone behind it who’s putting—directing—energy towards it. I can see you want to say something to someone, to reach somebody.”

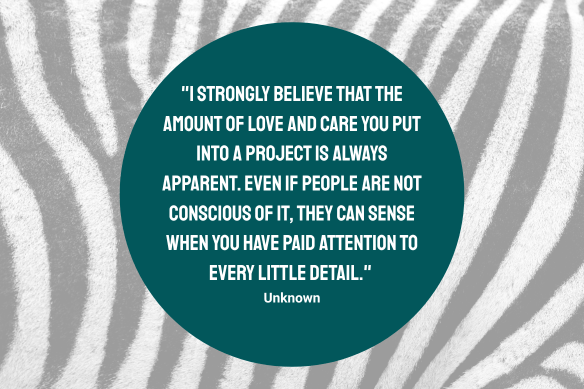

As he said this, I instantly remembered a quote that I read a few years ago and have highlighted in my Instagram profile (yes, I do go there in search of wisdom I have once read but forgotten).

“This is it,” I thought. There is someone who noticed. It’s one thing to read your stats and see how many people from around the world have read my texts; it’s entirely different to hear it—especially when it comes from someone sitting across from you, looking you in the eyes.

It came at the right moment, because just a few days before this meeting, there was another thought that wouldn’t leave my mind. I remember a friend of mine had a tagline on his social media saying “Whom do I write for if nobody reads these days?”

Thinking of these words didn’t discourage me, but it did impose another question—how and why do people read?

I’m not sure when the trend of reading as many books as possible began, but I did notice that it culminated during the pandemic. “This is a nice shift,” I thought. People are slowing down, enjoying the comfort of their homes and reading books. Then I started seeing the social media posts. Aesthetically stacked books.

“This is my April reading list.” “Finished.” “New achievement this July: I read twenty-eight books, almost one book per day.” Almost no one talked about the characters, the poetry itself, the power of a single verse, the book covers, the art, the authors and their biographies, but everyone talked about the grand achievement of reading many books in as little time as possible.

When did reading turn into one more ‘quantitative accomplishment’, as my fellow writer (whom I discovered during my research on this topic), Carry LIttlejohn says in his Reading for Reading’s Sake newsletter? Before I could find a psychologically-supported answer (although I think I had it already), Littlejohn solved this mystery for me, further explaining introspectively:

“…Or (and there’s probably something to this one) maybe it’s vanity. Maybe I want to have at my disposal the endless references and comparisons and anecdotes and examples from wide-ranging books that people can’t help but be dumbfounded by the breadth and depth of my reading life. Think old-school Christopher Hitchens or Salman Rushdie (as evidenced by this recent Book Riot podcast reviewing his latest, Knife). I dance between wanting the knowledge for the knowledge’s sake and wanting to be perceived as one having the knowledge (kind of like the intellectual counterpart to brute strength versus “show muscles,” neither of which I have, either).”

I have no doubt that most serious readers enjoy the act of reading. Discovering new worlds, feeling close to the author and their characters, exploring styles of writing and narration, learning and acquiring knowledge. Ultimately, they apply and convey the wisdom and insight gathered from a written piece of art.

So, if you consider yourself a serious reader—and you probably are since you arrived at this paragraph—I urge you: do not let the rush for achievements, the pressure to show off, or LinkedIn’s frenzy to ‘look smart’ within the frames of a pre-planned marketing campaign or online trend take over. Don’t race through pages. Let them teach you something. When you notice that your focus is decreasing, put down your book. You’ll get back to it—or leave it— if it no longer brings you joy or value.

“I read for pleasure and that is the moment I learn the most.” — Margaret Atwood

Instead, do what gives you peace. Do nothing. Do everything. Just don’t speed through the pages of a book like a racing car. Because if you do, you’re downplaying the author’s work. You’re missing out on slow mornings and restful evenings. You’re missing out on going over the same paragraph a few times because you want to understand it, rather than skip it. Or learning a new language and enriching your vocabulary without even realizing it.

You’re giving away the chance to lean into your chair, close your eyes and nap with the book in your hands—not caring about the world’s idea that reading should be treated solely as another weight on your cluttered to-do list.

Books of the Day:

Quote of the day:

“One reads for pleasure…it is not a public duty.”

― Alan Bennett, The Uncommon Reader

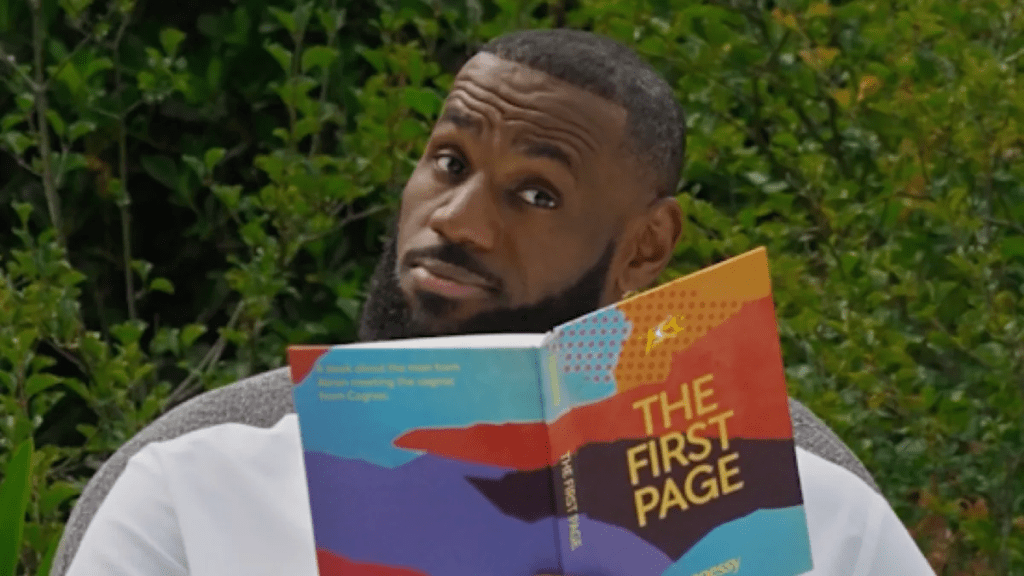

Meme of the day:

Leave a comment